A couple of days ago I was walking to an appointment. It was a beautiful day and a little bit in the distance I could see a Goodyear Blimp over a huge car dealership. I mentioned that to my mother when I spoke to her the next day, and she was reminiscing about the Hindenburg disaster that she clearly remembers. It happened about 50 miles from where she grew up. Radio broadcasters were present and gave a blow-by-blow commentary of the catastrophe. Newspapers had special editions, and anyone who went to the movies saw the newsreels. I’m not sure how many of you may know about it.

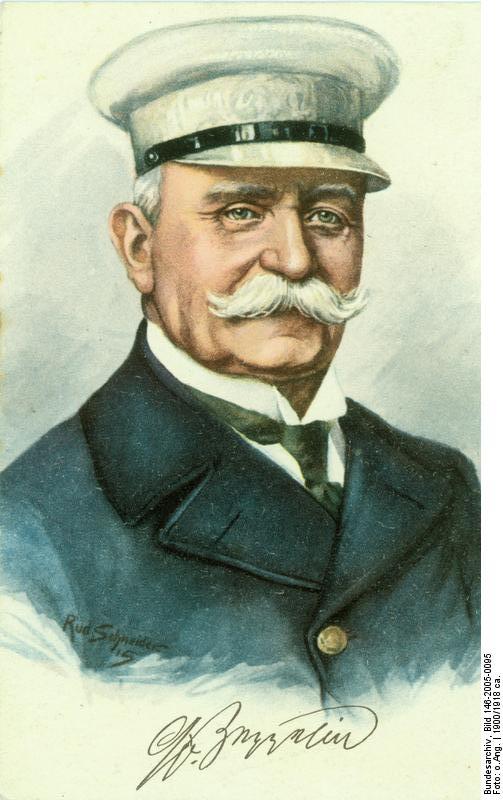

The Hindenburg, officially the LZ 129 Hindenburg, was an “airship” generally called a zeppelin. It was named after Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin (1838-1917) who developed the lighter-than-air rigid dirigible. Born in what is now Germany, he became an Army officer in 1855, and three years later took additional training in engineering at the University of Tubingen. During the American Civil War, Zeppelin was an observed with the Union Army. After the Peninsula Campaign, he toured part of the Midwest and in August, 1863, while in St. Paul, Minnesota, he went up in a balloon for the first time. After the war, he returned to Prussia and fought in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, and in 1870-71 served in the Franco-Prussian War. He retired from the German military in 1890, and turned his attention to developing a rigid airship.

Basically, Zeppelin intended to build a “ship” built out of aluminum beams and struts covered with extremely stiff fabric. The interior would have the engines and the appropriate number of gas cells (they used hydrogen at that point) that could expand or contract as needed. There would be a gondola containing controls and space for a crew. The inventor received his first patent in 1895. The first flight of an airship, LZ-1, took off near Lake Constance on July 2, 1900. It remained in the air for roughly 20 minutes. Now with a number of donations, Zeppelin continued to improve the ship. It flew for a full 24 hours in 1906, at which point the German government ordered a number of what was now generally called zeppelins. By 1914, 37,250 people had taken 1,600 flights in Europe with no problems. During WWI, the German military used 100 airships. Unfortunately, Zeppelin died in 1917, before seeing his dream of intercontinental flight. The Treaty of Versailles claimed the German military zeppelins as part of their war reparations, but a private company, the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin continued to build zeppelins for commercial use.

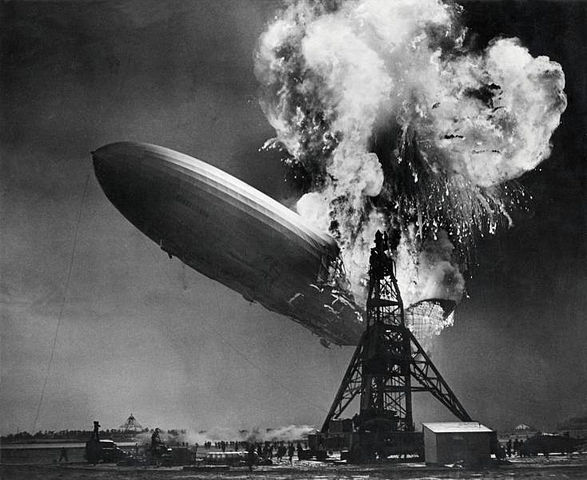

In March, 1937, the LZ 129 Hindenburg had taken a round-trip from Germany to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and on May 3d it left Frankfurt for the US, expecting to land at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on the morning of May 6. It had been a uneventful trip until the morning of the 6th when Capt. Max Pruss heard that there was bad weather, including thunderstorms, on the east coast. Instead of going straight to Lakehurst, he decided to take a “scenic” route so that the bad weather would be gone by the time they would arrive at Lakehurst. He took the Hindenburg straight over New York City. People in the city were thrilled, and came out of their buildings to see a zeppelin so close. From there, Pruss moved toward the New Jersey shoreline, and the passengers could see areas like Long Branch, Asbury Park and Point Pleasant. By 6:30 it appeared that the storm had passed. However, since they were almost 12 house late, the Captain decided that the public would not be allowed to go aboard the ship, or even walk around the mooring station.

They crew started its final approach at 7pm. They decided that they would do a “flying moor” which mean that they would drop the landing ropes and mooring cables from fairly high above the ground and the ground crew would use winches to gradually pull the ship to its mooring. At 7:21, when they were 295 ft above the mooring they dropped the lines, but one of the line was too tight. A light rain started to fall as the ground crew grabbed the lines. Four minutes later, something happened. Some people thought they saw fabric waving from the upper fin—signs of a gas leak. A few said they saw a blue flame. Others believed that they saw a spark from static electricity. Still others thought they saw flames from the port side. Whatever it was, the ship engulfed in flames. Gas cells started catching fire and the ship broke apart and collapsed in seconds. Thirteen of the 36 passengers and 22 of the 61 crew died. Many who survived were seriously burned. Initially investigators thought it may have been sabotage, or possibly engine failure or a fuel leak. Over the years, most have concluded that it happened either because of static electricity or a lightening strike. The one major change since then is that helium is the gas that’s used because it is inert and infinitely safer than hydrogen.

As I said earlier, because this was the first zeppelin of the season, there were numerous news crews waiting for the ship–radio, newspaper and crews from Pathe, Movietone,Hearst and Paramount. Herbert Morrison from WLS radio in Chicago, was an eyewitness and spoke directly to his listeners as the ship went down. If you want to dive deeper into the Hindenburg, you’ll find a great deal of information and lots of videos.