The Suez Canal is one of the most important thoroughfares on earth, moving more 10% of the world’s cargo every year. Last year more than 18,500 vessels covered the 120-mile-long canal from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. Last week, an ultra-large container ship, the Ever Given, on its way to the Netherlands from Malaysia ran aground after turning sideways while struggling with the wind. No ships have been able to move north or south since then, and maritime experts from around the world are trying to find a way to reopen the canal. That’s caused a $10 billion dollar lost in little more than a week.

People have been interested in a canal since the days of ancient Egypt. Several Pharaohs attempted a canal, though only Darius I managed to develop something similar to a canal. Venetians, the Ottomans, even Napoleon attempted to build a canal but for a variety of reasons, particularly cost, engineering, and manpower, none ever managed to built such a canal. There were several goods about attempts to build a canal, and while waiting under quarantine in Egypt, a young assistant consular agent, Ferdinand de Lesseps, spend his time reading Napoleon’s civil engineer, Jacque-Marie Le Pere’s book, The Ancient Suez Canal. De Lesseps was hooked.

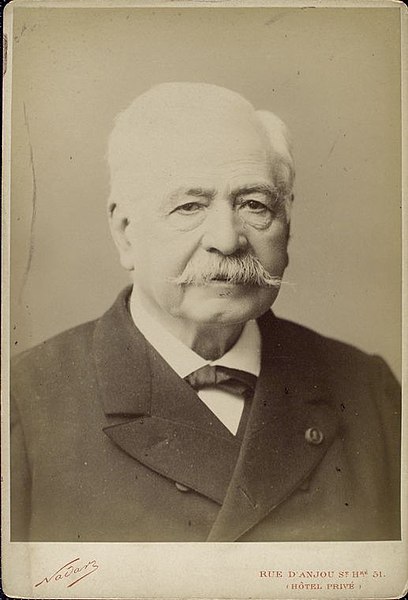

Ferdinand Marie Vicomte de Lesseps (1805-1894) attended the College of Henry IV in Paris, and initially worked in the Commissary Department of the French Army. In the following years he served as the vice-consul in Lisbon, Tunis, and Alexandria. He became consul in Cairo, Rotterdam, Malaga, and Barcelona, and served as the French Minister to Madrid. However, after major elections in 1849, de Lesseps retired from public office.

While he had worked as assistant consul in Alexandria, he had become very friendly with Sa’id Pasha who, in 1854, became Khedive (viceroy) of Egypt. He and de Lesseps were extremely interested in a canal, so de Lesseps returned to Eqypt, and on November 7, 1854, the Khedive signed a bill giving de Lesseps the concession to build a canal. He immediately called in thirteen engineers to develop appropriate plans which were adopted by the International Commission of the piecing of the Isthmus of Suez in 1856, and on December 15, 1858, de Lesseps established the Suez Canal Company.

Work started in April 1859. Roughly 30,000 people from a variety of nations worked on the canal. Many from Egypt worked on the canal as required by the “corvee” —a specific amount of unpaid labor owed to the government in lieu of taxes. Sadly, they’re were thousands of deaths over the year, due largely to cholera. The canal doesn’t require locks and initially there was just a single lane, but it quickly made sense to included passages at the Ballah Bypass and the Great Bitter Lake, to allow limited north-south passages. The north terminal is at Port Said, with Port Tewfik at the southern end.

The Suez Canal opened on November 16, 1869, with a blessing of the waters of the canal by both Muslim and Christian clerics. It was followed a lavish banquet including the Khedive, the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph, the French Empress Eugenia and the Crown Prince of Prussia, along with other dignitaries who watched lavish fireworks. The following morning, ships set sail for the half-way point at Lake Timsah. However, the French ship Peruse anchored too close to the entrance, accidentally swung around and ran aground, blocking the way into the lake. The rest of the ships anchored in the canal itself, and managed to drag Peruse clear the next morning.(Portent of things to come??) They sailed on to Port Tewfik on the 19th. The following day, the S.S. Dido was the first ship to pass through the canal from south to north. Once the Suez Canal was in full swing, it cut 5,500 miles off the trip from Europe to the Far East.

One of the most important political issues regarding the Canal came in 1888 with the Convention of Constantinople, in which all of the European powers signed a treaty agreeing that the Suez Canal would be a neutral zone, even during times of war. However, during both World Wars, it was closed, as well as during the 1956 Suez Crisis. That ended with the first United Nations Peacekeeping Force which assumed control of the Canal and maintained open access for all until both Egypt and Israel withdrew.

Thanks to the tides, tug boats, a number of engineers and salvage teams and dredgers, the skyscraper/cargo ship is righted, and will move into the Bitter Lake, the widest area of the canal so that it can be thoroughly inspected while the hundreds of waiting ships can start moving again.