They started to inoculate the first group of people with the Pfizer covid-19 vaccine on December 14th, and the Moderna vaccine is on its way. We really are standing right at the end of the tunnel–and it’s taken all of TEN MONTHS to do it! I’m old enough to remember the Polio epidemic of the 1950s and the breakthrough vaccine. How very different it is today, both in the development of the vaccine and its distribution.

People have known about polio for years, but it became increasingly rampant in the beginning of the 20th century. Everyone was shocked when Franklin Roosevelt was diagnosed with polio in 1921. You’ll rarely see pictures of him standing–most of the time he’s sitting at a desk or in a car. On those rare photos where he is standing, he’s actually wearing very heavy metal braces and holding someone’s arm.

In 1938 Roosevelt established the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to raise money for research and assistance for children with polio. It was the entertainer, Eddie Cantor, who came up with the name The March of Dimes. Cantor suggested that people send dimes to the President for his birthday on January 30. FDR liked the idea, but was extremely surprised that $85,000 in dimes (nickels and quarters too) arrived at the White House for his birthday. Between 1938 and 1955, when Dr. Jonas Salk announced that his vaccine worked, the March of Dimes received $233 million dollars to find a cure.

The number of polio cases grew rapidly in the 20th century, and it almost always affected children. In 1952, 57,000 children were infected, 21,000 were paralyzed, and 3,145 died from it. It was always worse in the spring and summer, and jittery parents refused to allow their kids to play in pools, or going to theaters. They were terrified that their children might spend the rest of the lives in “iron lungs” which were the only way some of them could breath. I lived about a mile away from a hospital called the Children’s Country Home (now the Children’s Specialized Hospital) in Mountainside, where children received important physical therapy. There were also too many children who needed the assistance of an iron lung.

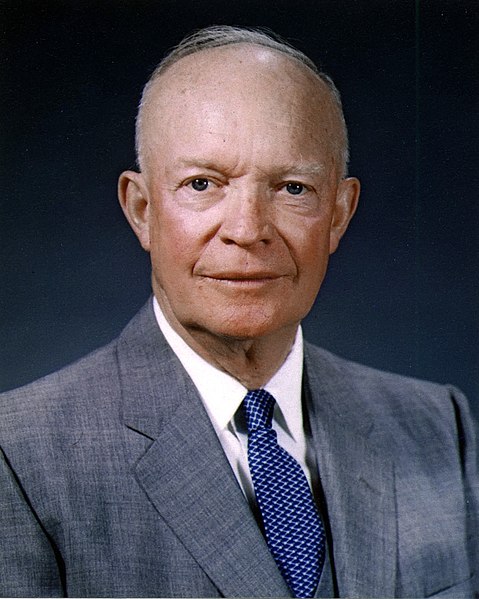

One of the best day for millions of parents was April 12, 1955, when President Dwight Eisenhower and Jonas Salk stood in the White House Rose Garden and announced the vaccine. A father and grandfather himself, Ike told Salk, “I have no words to thank you. I am very, very happy.” High praise from the General who had commanded the European Theater during World War II.

Speaking to Edward R. Murrow, Salk told him that the doctors and researchers had done their jobs. Now the government had to figure out how to get it to those who needed it. Many people thought that the government had been quietly stockpiling a huge number of doses of the vaccine to immediately give to all children. Not so. On April 13, Oveta Culp Hobby, the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare (now Health and Human Services) told Congress that states and individuals should be in charge, not the federal government. The President was not happy. Having spent his life in the Army, he understood the importance of logistics. He told her to put together a sensible plan ASAP, because summer was coming and polio was always worse in the summer. When she didn’t move fast enough, he called a Cabinet meeting and again told her to get it done. She finally developed a plan to assist impoverished children, but insisted that the government should not be involved. By July 1955, 4 million children had been vaccinated, and Hoppy had resigned.

Eisenhower was not satisfied. He was getting information that parents were so concerned that black markets for the polio vaccine had been popping up in some areas. In 1955, the shot cost $2.00 on the open market, yet they were going for up to $20.00 in the black market. (Remember, the median income in 1955 was $3,400.) The President signed the Polio Vaccine Assistant Act of 1955 under which $30 million dollars would fund the vaccine. By the following summer, 30 million children (including myself) had been vaccinated.

Fast forward 65 years. The world is dealing with a pandemic not seen for 100 years. How to develop a vaccine? Once you have a vaccine, how do you distribute it? Should it be done the was it was during the Polio epidemic? Under that scenario it would have taken four to five years to develop a vaccine, and only then would anyone think about how it should be distributed. Yet today, the first of at least four vaccines has rolled out in barely 10 months. People have complained that we had a slow start. Well, we also had a slow start at the beginning of World War II. Yet once they got things up and running they were finishing roughly three Liberty ships every two days, and built 300,000 planes between 1941 and 1945. How did they do it? A public-private partnership and American logistics. Sound familiar?? For one minute, just one, let’s act like adults and agree that Operation Warp Speed did the job–and did it faster and better than anyone expected. Whether you like or hate the current President, be honest and give the devil his due. He got something done that no one believed would be possible. It wouldn’t hurt to say thank you for that.