Finland and Sweden (those are their flags) have just requested entrance into NATO. If they do ultimately join, they will be the 31st and 32d members. Most of us know something about NATO, but how did it come about? Well, you really need to go all the way to the meeting at Yalta in February 1945.

At the meeting of the Big Three (Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin) the Soviet leader demanded, and the other men finally gave in, that at the end of the war, Poland would be under Soviet control. The Polish Government-in-Exile had worked side by side with the Allies, and had treaties with both Britain and France, but at that point, with Soviet tanks barreling through Poland on their way to Germany, there was little that the US or UK could do. However, neither Churchill not Roosevelt, and later Truman, were happy with the Soviet takeover. They were even more concerned with the way a Soviet-backed coup turned Czechoslovakia into a communist underling, and how the USSR set up the Berlin Blockade. Western European states feared that the Soviets would try to take over more nations that were still on their knees after the war. So in 1947, the United Kingdom and France signed a defensive pact known as the Treaty of Dunkirk.

The Benelux countries–Belgium, The Netherlands, and Luxembourg–are small nations and, concerned with possible Soviet inroads, wanted additional military support from other major nations. On March 17, 1948, they joined with Britain and France and signed the Treaty of Brussels, which was a mutual defense pact which would last for fifty years. That was an excellent first step, but as most of Eastern Europe remained under the control of the Soviet Bloc, many in the West felt that they ultimately needed to work together with the US to stand up to Stalin.

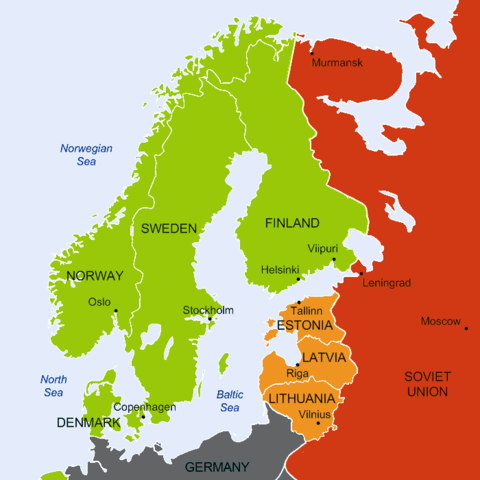

After another year of consultations, the US signed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization–NATO. In addition to the UK, France and the Benelux countries, Canada, Italy, Portugal, Denmark and Iceland joined the Organization. Greece and Turkey joined in 1952, and West Germany did so in 1955. So, during the peak of the Cold War, NATO faced the Warsaw Pact. Spain became a member of NATO in 1982. But it wasn’t until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 that former members of the Warsaw Pact joined NATO. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland joined in 1999. Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia entered in 2004. NATO accepted Albania and Croatia in 2009 while Montenegro joined in 2017 and North Macedonia in 2020.

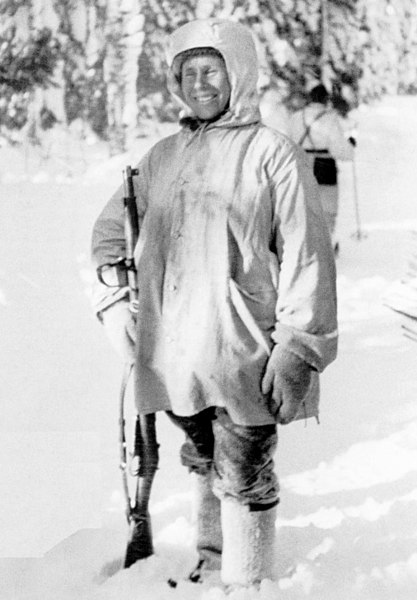

Shortly after the fall of the USSR, it seemed to be possible that the West and Russia would be able to work well. But with Mr. Putin’s attacks in Georgia, Chechnya, and early forays into Ukraine, it’s no wonder that Sweden and Finland, both of whom had fought Russia to a stalemates in the past, would want to join an organization that could stand up against possible aggressions to come from Russia.