Tun Tavern, November 10, 1775, saw the birth of the United States Marine Corps. So many of us think of Marines at Belleau Wood, Iwo Jima, Inchon, Da Nang and Fallujah, but Marines have been in so many more areas of the world. Sometimes it’s been in battle, but frequently they went to show the flag. One long-forgotten diplomatic mission happened in 1903-1904 in Abyssinia (Ethiopia).

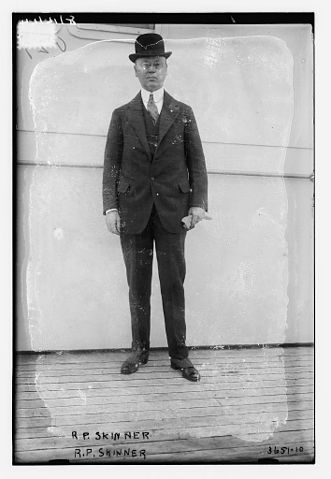

In the summer of 1903, the US decided to establish relations with the nation of Abyssinia. Few people knew much about it, though it was a well functioning nation which had actually defeated the Italians in 1894 when Rome thought it would be a cake-walk to seize the Abyssinia. The US much preferred to be a trading partner. The State Department told Consul Robert P. Skinner, then in France, to travel to Addis Ababa, capital of Abyssinia, and develop a treaty.

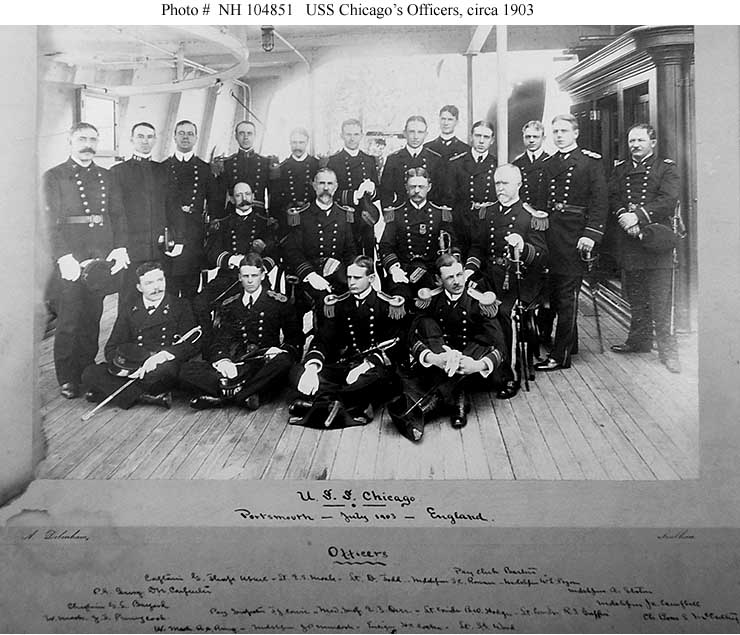

At that same time, the U.S.S. Brooklyn, U.S.S. San Francisco, and U.S.S. Macias were off the coast of Beirut, and they were ordered to put together a detachment of Marines, with a few seamen, to join Skinner on his trek to Addis Ababa. Lt. Charles L. Hussey, USN led the party. With him was Capt. George C. Thorpe, USMC, one sergeant, two corporals, 14 privates, six sailors, one hospital steward, a coxswain and an electrician. They sailed aboard Macias through the Suez Canal and down the Red Sea to Djibouti in what was then called French Somaliland. There they met up with Skinner and his secretary, Horatio Wales.

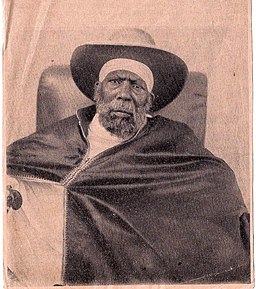

From Djibouti they took a rickety, narrow-gauge train about 200 miles to the end of the line at Dire Dawa, which was filled with mud huts, a telegraph office and a telephone exchange. There they set up Camp Scott. The following day they enlisted a translator, and bought 45 mules and 46 camel for their 300-mile trek to Addis Ababa. Shortly after they started their journey, they received a message from Ras Mekonnen asking the Americans to make a 32-mile detour to Harrar. As the most trusted counselor to the Emperor Menilek II, and the man who had defeated the Italians at the Battle of Adwa, that was a “command performance.” The Ras and 100 of his soldiers met the Americans just outside the city, and led Skinner and the entire detachment in to Harrar. The Consul and the translator spoke at length with Mekonnen and the following day returned to Dire Dawa. They finally headed out to Addis Ababa on November 29.

Most of the camel and mule handlers were members of the Danakil tribe, who were more warriors that muleteers. At one point, the man in charge of the animals told Thorpe to head in a different direction. When Thorpe insisted that they follow the American’s route, the man pulled a knife on the Captain. He and another Marine grabbed the knife. The man then snatched one of his own men’s spear. The Marines grabbed that as well, at which point the man gave up, flopped on the ground crying and carrying one—and then got up and started heading in the right direction.

Things went well until the evening of December 3d when the Danakil and what seemed to be a large group of men in the area began to threaten the Marines. Hussey, Thorpe and Skinner were discussing whether they might need to fight their way back to Dire Dawa when they started hearing very loud voices in a language even the translator didn’t understand. There seemed to be numerous people wandering around the area. Thorpe and his men formed a skirmish line and were seconds away from moving out when the clouds moved and they saw a huge number of monkeys who took one look at the Marines, and fled.

They trekked on across the grassland, until early in the morning of December 18, when they arrived about a mile away from Addis Ababa. Taking some time to change into their dress uniforms, they were met by Abyssinian troops and a group of Emperor Menilek II’s counselors, all dressed in brilliantly colored uniforms and the cavalry riding a variety of animals from Arabian steeds to zebras. After a “formal picnic” the Americans were escorted into Addis Ababa straight to the Geubi, the Emperor’s palace, where they met Menelik II. After a 21-gun salute and shaking hands will all the Americans, Skinner presented the Emperor with a large silver tray engraved with an invitation for Abyssinia to join the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in the spring of 1904. The Emperor immediately agreed. After some additional discussions with Skinner, the Emperor withdrew and the Americans marched to another palace to the tunes of Hail Columbia and the Marseilles.

Skinner and the Emperor continued their talks the following day. They agreed to establish diplomatic relations, and agreed to Most Favored Nations status between the two countries. Later that day, the Americans met diplomats from Italy, Great Britain and Russia, as well as the Abuna, Archbishop Mathias, the head of the Coptic Christian Church, and one of the most influential men in Abyssinia. On the 23st the Americans attend a mpressive banquet. The following day Emperor visited Camp Roosevelt, where he watched the Marines parade and Thorpe put his men through the Manuel of Arms and Bayonet exercises. Cpl. Joseph Rossell (later Colonel, USMC) showed the Emperor the Krag-Jorgenson rile, disassembling it, answering Menilek’s technical questions, then reassembling it at breakneck speed, loading it with blanks, and handing it to the Emperor who enjoyed shooting over the heads of some of his own men.

After additional discussions, Menilek and Skinner signed the treaty on December 27. The Emperor then presented each Marines and Seamen with the Menilek medal, and presented Hussey and Thorpe with the Star of Ethiopia medals, and two spears. As they were about to leave, the Americans were also presented with two massive elephant tusks, and two lion cubs to be presented to his friend, Theodore Roosevelt. The camels which were to carried the cubs in large baskets were terrified. Camels and lions don’t mix, but eventually they relented and carried the cubs, swaying along, back to Dire Dawa. (One of the cubs became terribly seasick because of the constant swaying, and eventually died. The Emperor replaced it, and both lions spent the rest of their days at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.) By January 15, the Americans were back in Djibouti, boarding the Macias, and heading back to Beirut. Mission accomplished.