August is the 107th anniversary of the commercial opening of the Panama Canal. It was initially discussed in 1513, when Vasco de Balboa was the first to walk across the Isthmus of Panama and people began thinking about ways to build a canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Yet it wasn’t until the 19th century that any serious work began.

Recently you may remember I was talking about Ferdinand de Lesseps who built the Suez Canal which began operations in 1869. Well, a few years later he decided that it would be a great ideal to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. In 1876 he set up La Societe international du Canal interoceanique. He received a concession from Colombia, of which Panama was a province in those days, and set to work.

De Lesseps believed that he would again be able to build the canal at sea-level, but he wasn’t an engineer. He didn’t realize that even at the best spot to do the work it was still more than 360 feet above sea level. In addition, they also and would have to divert several rivers, the largest of which was the Chagres. And on top of that, malaria and yellow fever were rampant. Regardless, work started on January 1, 1881, and by 1888 40,000 men were toiling away at various parts of the canal. Sadly, between 1881 and 1888, 22,000 men had died, largely from malaria, yellow fever, and accidents. The company went bankrupt in 1889, and while de Lesseps tried to start over in 1894, the new venture failed within a year. Millions of cubic yards of dirt, and hundreds of buildings, machinery, even trains, were left to the mosquitoes. But not ten years later, work on the Panama Canal was well on its way to completion.

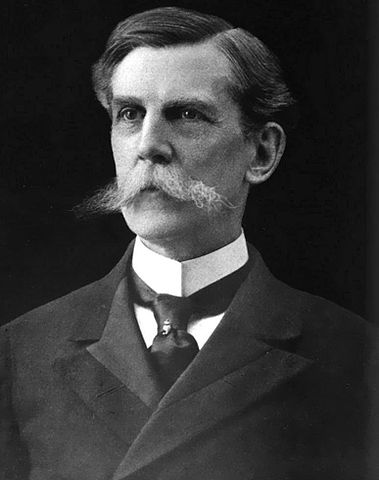

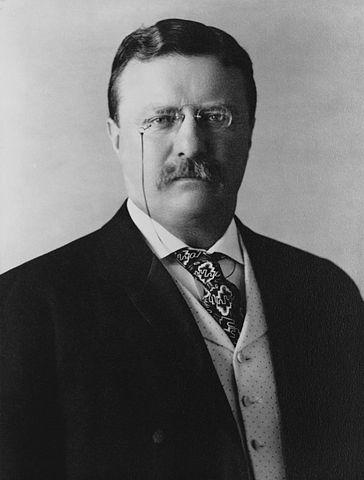

What happened was a combination of a break-away of Panamans from Colombia, and President Theodore Roosevelt. He believed that it would definitely be in the US strategic interest to have a canal so that ships could sail from the the east to the west of the US in a matter of weeks (less than a week these days), rather than having to take at least three months to sail all the way around Straits of Magellan. Negotiations between the US and Colombia resulted in the Hay-Herran Treaty in early 1903, but the Colombian Senate did not sign it. At that point, the Panamanians who were trying to break away from Colombia took the advantage to declare it’s independence on November 3, 1903. On the 18th of November, they signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty before the Colombian military could even get their troops to either Colon or Balboa.

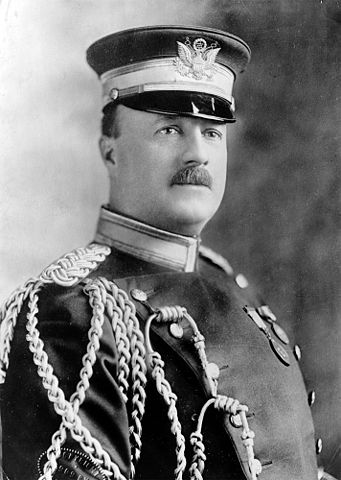

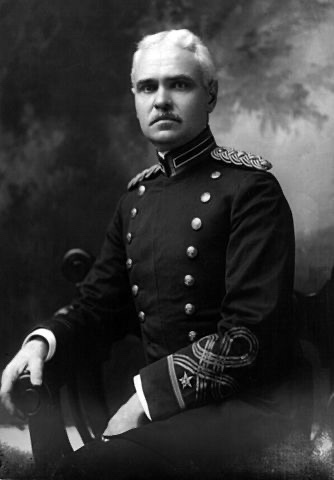

By May 1904 the Isthmian Canal Commission was up and running. John F. Stevens, the engineer who had built the Great Northern Railroad took charge. He immediately started rebuilding the houses, cafeterias, hospitals, old water system, repair shops and trains that de Lesseps had left. In 1907 Stevens resigned, and then-Colonel George W. Goethels took over. He had graduated from West Point in 1880 and served in the Corps of Engineers. Under his watch, the canal was built with locks, which would raise and lower ships 85ft above sea level allowing passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Ultimately, the men had excavated 170,000,000 cu. yds. of dirt, in addition to the 30,000,000 that the French had moved, the locks worked well, they had finished the massive Culebra (aka Gaillard) Cut and were proud of the fact that they had finished the canal two years earlier than expected.

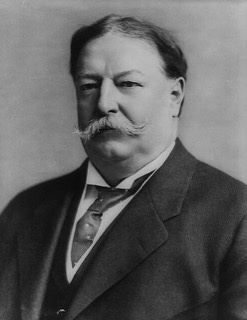

One of the reasons that the work moved along quickly was thanks to Colonel William Gorgas, an expert in tropical diseases. He had worked with Walter Reed to find the origin of malaria and yellow fever, so when ordered to Panama, Gorgas went to war against mosquitos. He oversaw the building of a state-of-the-art water system, fumigated buildings, installed thousands of screens, ordered that people use mosquito netting when sleeping, eliminated stagnant water, and sprayed for insect infestations. Though more than 5,500 workers died by the time the canal opened, it was a massive improvement from the days of de Lesseps. Since then, the US has expanded the canal, and has turned it over the Panama, but we should still thank all those visionaries.

For some fascinating information, take a look at http://McCullough. The Path between the Sea