Next week, the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff(JCS), General Mark Milley, is going to be on the hot seat in Congress regarding his involvement in the US debacle in Afghanistan. Add to that the comments in the new Woodward and Costa book regarding the General’s conversations with his opposite numbers in China. Some say they were standard discussions. Others believe that he was trying to overthrow the duly elected president and at the very lease should resign immediately. Should he stay? Or should he go? The Congressional hearings will be key to his future.

Yet a number of my students—friends, too, don’t really know how the JCS came about. For that we really should go back to the War of 1812. The war’s ground campaigns were key, yet the naval battles on Lake Champlain under Capt. Thomas MacDonough were a major component of the ultimate success of the War. President Madison and the Secretaries of War and the Navy understood that joint operations were vital. Nor can we forget the importance of the joint operations of General Ulysses S. Grant and Admiral David D. Porter during the Battle of Vicksburg. By 1900, war had become so complicated that it was clear that joint operations could not be done on an “as needed” basis. In 1903, the US established a Joint Army and Navy Board that could set up joint ops. However, it wasn’t a fully integrated Board. Rather it was simply a planning board which could discuss issues. By the Great War, is still was not truly involved in the actual conduct of joint operations. After the War, the Secretaries of War and of the Navy redefined the Joint Board. It now included the two services’ Chiefs, Deputy Chiefs, the Chief of War Plans Division of the Army and the Director of Plans Division of the Navy. The Joint Board could now make recommendations for joint operations.

This was headed in the right direction, until the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. In the Arcadia Conference (December 22, 1941-January 14, 1942) President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill set up the Combined Chiefs of Staff. For some time, the British Chiefs of Staff had established administrative, strategic and tactical coordination. It was clear to the Americans that to work closely with the Combined Chiefs, they would finally have to expand and coordinate the US Army and Navy planning and intelligence structures in an effort to provide advice to the Secretaries of War and the Navy, and to the President himself. To do so, the US set up a combined high command in 1942 that was called the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. Roosevelt wanted someone to be in charge, and looked to Admiral William Leahy.

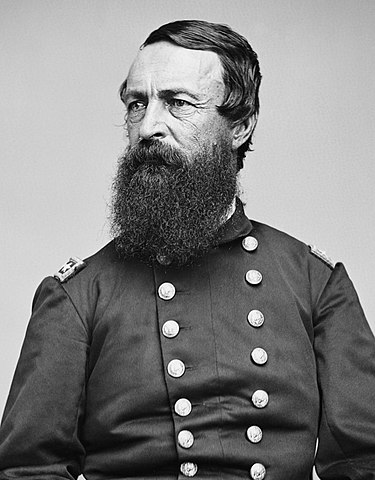

Leahy was born in Iowa in May, 1875, and was graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1897. He served in the Spanish-American War, the Philippines, China, Nicaragua, Haiti and Mexico. During World War I, Leahy captained a dispatch boat that the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Roosevelt used, and they developed a lifelong friendship. During the inter-war years Leahy held numerous posts and by 1937 he became the Chief of Naval Operation which he held until his retirement in 1939. Roosevelt then named him governor of Puerto Rico which he held until January 1941 when the President found that Leahy would be the best man to serve as ambassador to France–that is Vichy France. As ambassador he worked tirelessly to try to lessen the grip the Nazis held Vichy, but to no avail. After Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt ordered Leahy home, to serve as his senior military officer who would liaise with the chiefs of the Army and Navy. The US needed someone to work both with the President, and the chiefs, as well as the Combined Chiefs. All agreed that Admiral Leahy was the man for the job. He became the Chief of Staff to the Command-in-Chief of the United States on July 6, 1942.

With years of experience as a naval officer, and an innate understanding of diplomacy, he was able to wrangle all three US chiefs of staff–General George Marshall (USA), General Henry (Hap) Arnold (USAAF) and Admiral Ernest King (USN), and worked extremely well the the Combined Chiefs from the UK. When President Roosevelt died in April, 1945, President Truman requested that Leahy continue as Chief of Staff which he held until he retired again in March, 1949. He died at the Bethesda Naval Hospital in July 1959.

After the war, Leahy published his memoir, I Was There, which is one of the most honest memoirs I’ve read. He was not trying to add “spin” to any answers, wasn’t trying to “cover his six” by shifting responsibility to others. He was not a “political Admiral” like so many are these days. What would Leahy have thought about General Milley?

You may be interested in Leahy’s book, or a full biography of the Admiral as listed below